Noble’s Restructuring Now Effective; Lessons for Future Schemes

At a Glance

Kirkland & Ellis advised Noble Group Limited, the major global commodities trader, on its successful multi-billion dollar financial restructuring. The restructuring effective date occurred on 20 December 2018.

The cross-border restructuring, described by the English court as “of the utmost complexity,” involved moving the Bermuda-incorporated, Singapore-listed company’s centre of main interests from Hong Kong to London, implementing parallel English and Bermuda schemes of arrangement, recognition of the English scheme in the U.S. via Chapter 15 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, and, ultimately, a so-called "light touch" Bermuda provisional liquidation procedure.

The scheme of arrangement raised several crucial issues that were the subject of detailed consideration by the English court, principally: class constitution, scheme process, restructuring timetables, third-party releases, and disclosure of fees. This Alert summarises those issues and highlights the key lessons for future schemes.

The restructuring was described by the English court as "of the utmost complexity"

Noble was by any measure one of the most complex restructurings in recent memory. Not only was the underlying restructuring unprecedented in terms of its scale, urgency and complexity, but uniquely the provisional liquidator was asked to take steps to complete the restructuring in place of the company where schemes of arrangement had previously been sanctioned by the courts.

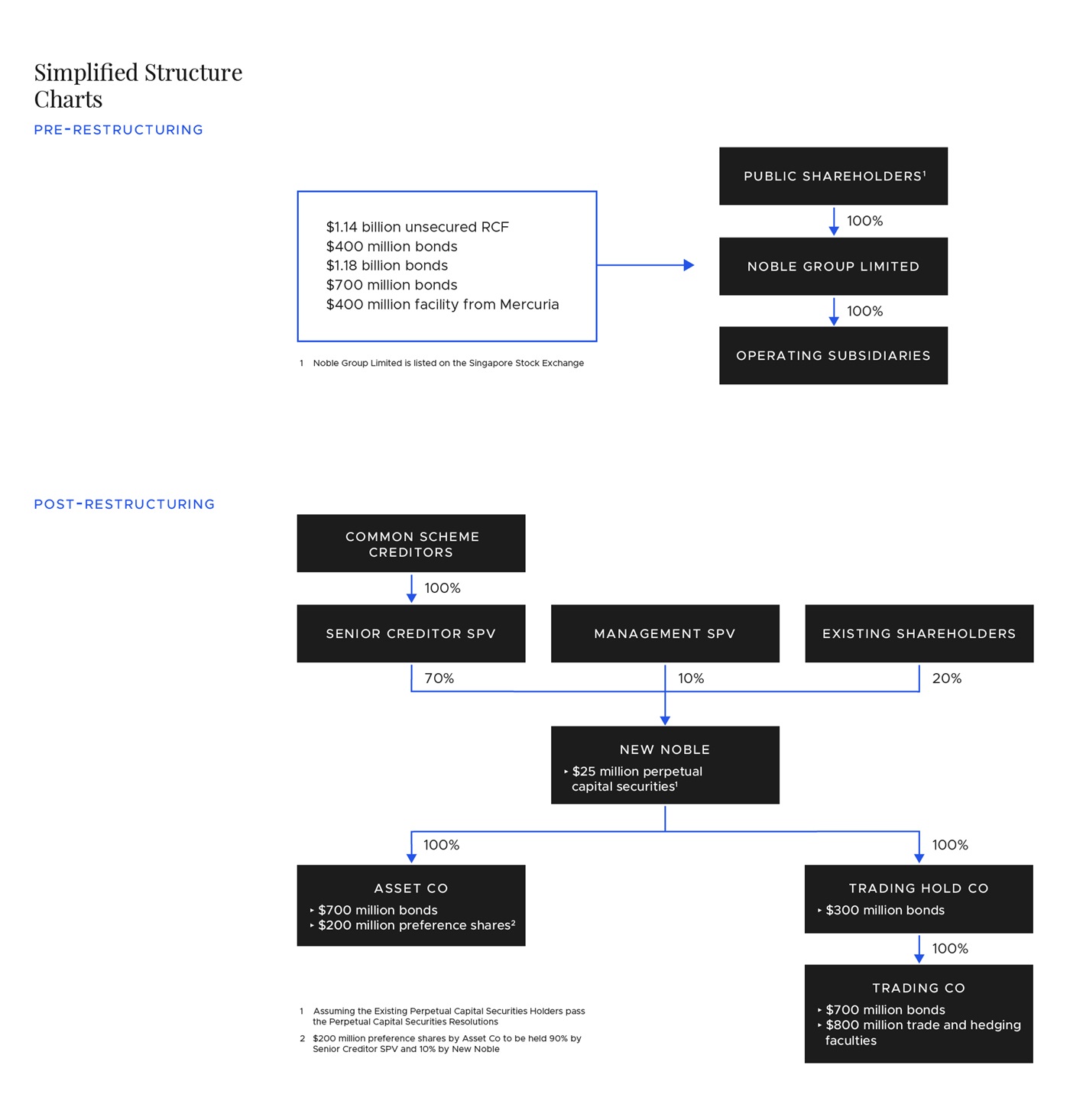

Pre-restructuring debt

The restructuring compromised:

- three series of notes, with $2.3 billion total principal outstanding;

- a $1.14 billion revolving credit facility;

- $400 million perpetual capital securities; and

- (unusually) certain contingent liabilities to non-finance creditors who had asserted claims against the Company, including in respect of certain guarantees and certain litigation.

The scheme required creditors to submit their claims and supporting documents before a certain “bar date” (following the effective date of the scheme); the claims would then be subjected to a claims determination process modelled on the procedure by which such claims would be determined in a liquidation in England.

Only those creditors whose claims were accepted received a portion of the consideration under the scheme.

Unusually, the restructuring compromised certain liabilities to non-finance creditors

Post-restructuring debt and equity

The consideration under the scheme comprised:

- $290 million of bonds issued by an intermediate holdco of New Trading Co;

- $1.28 billion of bonds issued by New Trading Co itself and New Asset Co, which are structurally senior to the bonds issued by the intermediate holdco of New Trading Co, and which were only issued to creditors who elected to “risk participate” by agreeing to guarantee new money debt (in the form of $700 million of new trade finance and hedging facilities); and

- shares in the Senior Creditor SPV (which owns 70 percent of the new holding company ("New Noble")).

The $400 million perpetual capital securities were excluded from the schemes, because they were substantially “out of the money” (i.e., below the “value break” in a liquidation analysis). They were instead subject to a separate exchange offer and consent solicitation.

Simplified pre- and post-restructuring structure charts are in Annex 1.

The English court's comprehensive judgments included comments that will invariably inform the market's approach to future schemes of arrangement

Delivering the global restructuring

The Company’s shareholders approved the transfer of the Company’s assets to the New Noble group in August. This obviated the necessity for a pre-packaged administration sale, which was the fall-back option underpinned by the COMI shift.

The English and Bermuda schemes of arrangement were approved by an overwhelming majority of scheme creditors: 99.98 percent by value, and 98.52 percent by number. The English scheme was sanctioned on 12 November; the Bermuda scheme was sanctioned on 14 November. No creditor formally challenged either scheme.

The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York granted recognition of the schemes in the U.S., via Chapter 15 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, on 15 November.

The process was complicated by the fact that, following sanction of the schemes, the Singaporean authorities decided not to allow the Company to transfer its listing status to New Noble. The Company's board remained of the strong view that the restructuring was in the best interests of all of the Company's stakeholders. Accordingly, the Company sought the appointment of provisional liquidators in Bermuda, to implement the restructuring in accordance with the terms of the schemes. (This included the allocation of 20 percent of the equity in New Noble to the Company's existing shareholders.) The restructuring effective date occurred on 20 December 2018.

Lessons from Noble

The English court’s comprehensive judgments by Mr. Justice Snowden included comments that will invariably inform the market’s approach to future schemes of arrangement, especially in the most complex cases.

1. Class Constitution

Class constitution: the basics

It is for the company (with its advisers) to determine which creditors to include in a scheme, and whether they need to be separated into different classes for the purpose of voting on the proposed scheme. Only creditors whose rights against the company are “not so dissimilar as to make it impossible for them to consult together with a view to their common interest"1 may vote in the same class. The focus is on a comparison of the existing rights of creditors to be altered/extinguished by the scheme, and the new rights to which creditors will become entitled under the scheme.

The statutory majorities required to approve the scheme (at least 75 percent by value, and a majority in number, of those creditors who vote) must be achieved for each class before the company seeks the court’s sanction for the scheme. The modern trend is to resist any tendency to increase the number of classes, for fear that fragmenting creditors into multiple classes gives each class an (unwarranted) power to veto the scheme.

The court will consider any private interests or motivations creditors may have when it considers whether to sanction the scheme.

In Noble, the judge carefully considered appropriate constitution of the creditor classes. Although the court would consider the private interests and motivations of creditors when considering whether to give effect to the majority vote at the sanction stage, the individual interests of creditors that are not shared by other members of the class were not to be taken into account at the convening stage. Not every difference between the rights or treatment of different groups of creditors would necessarily lead to a need for separate classes. The safeguard against minority oppression was that the court was not bound by the decision of the class meeting(s), but retained a discretion to refuse to sanction the scheme.

The court approved Noble’s proposed class constitution, which involved separating creditors into two classes.2 The analysis was particularly complex given the issues in Noble’s case (see Annex 2).

2. Scheme process: nature of the convening hearing

Scheme process: the basics

A scheme of arrangement process involves two court hearings. The first hearing is known as the convening hearing, at which the company seeks a court order to convene meetings of its creditors (and/or shareholders). The second hearing is known as the sanction hearing, which follows approval of the scheme by the requisite majorities of creditors (and/or shareholders) and at which the company seeks the court’s sanction for the scheme. The court’s sanctioning of the scheme is discretionary.

The function of the court at the first (convening) hearing is “emphatically not” to consider the merits or fairness of the proposed scheme.3 The primary function of the convening stage is to consider the question of the proper formulation of classes for the scheme meeting(s). It is not, however, limited to that issue: other jurisdictional or quasi-jurisdictional issues may be raised.

The court in Noble drew back from determining jurisdictional issues at the convening stage, cautioning against the convening hearing becoming the primary focus of the scheme process (rather than the sanction hearing). The implication is that, in future schemes, the court will consider the sanction hearing to be the more appropriate time to determine jurisdictional issues.4

The court held that all it could legitimately do at the convening stage was to indicate whether it was obvious that it had no jurisdiction to sanction the scheme. Here, the court was satisfied that no such “roadblock” existed.

At the sanction hearing, the court undertook a more detailed analysis of jurisdictional issues. It was satisfied that the Company had a “sufficient connection” with England to justify exercise of the scheme jurisdiction, that the scheme was likely to be recognised and have a substantial effect in other significant jurisdictions, and that it was appropriate in the international context to exercise the court’s discretion to sanction the scheme.

3. Restructuring timetable

Timing: the basics

The procedure and processes to be followed in a scheme of arrangement are laid out in a practice statement issued by the High Court in 2002 (the “Practice Statement”). The Chancery Guide also requires certain documentation to be lodged with the court in advance of hearings.

Flexibility and the ability to move swiftly when a genuine need arises is a particularly attractive and useful feature of the process for schemes of arrangement, as the court noted in Noble.

The timing of Noble’s restructuring, including the English scheme, was driven by the need to comply with conditions set by Singapore’s Securities Industry Council and the commercial needs of the business.5

Noble complied with the requirements of the Practice Statement. The court held the Company had given adequate notice to the creditors. It recognised that, although the scheme and the associated restructuring was of the “utmost complexity,” the Company had made regular announcements throughout 2018 explaining the progress of the restructuring. The court found that the practice statement letter was “as clear a document as the complexity of the matter permit[ted]."

Nonetheless, the court’s judgment in Noble will necessitate even closer management of scheme — and overall restructuring — timetables in the future, especially in complex cases with lengthy documentation. Advisers will need to inform the Court Listing Office well in advance, so that a suitable judge can be assigned and given a realistic amount of pre-reading time in their schedule. The court cautioned that the timetable for further steps in a restructuring should no longer presume that the court will give its decision immediately; as we know from earlier cases, the court’s role is not that of a “rubber-stamp.”

This will effectively mean wrapping up commercial negotiations at an earlier stage, to allow sufficient “runway” for the court process. Otherwise, there is a risk that the court may adjourn the hearing(s) until adequate time can be found — which, of course, may imperil the overall restructuring.

4. Third-party releases

The schemes included a release of scheme creditors’ claims against certain third parties. The English court commented that its jurisdiction to release claims against third parties within a scheme was not limited to guarantees and claims closely connected to scheme creditors.6 It acknowledged that “such clauses can be justified by a need not to undermine the terms of the scheme itself and have become a regular feature of schemes.”

Issues might, however, arise where a scheme creditor has a more tangential claim against a third party.7

5. Fees

The payment of fees to creditors is subject to particular scrutiny in schemes of arrangement, for the purposes of appropriate class constitution, fairness and adequate disclosure.

In Noble, the court called for additional disclosure regarding:

- the fees payable in respect of the scheme and the broader restructuring;

- the circumstances leading to the payment of such fees;

- the identity of the ad hoc group of creditors and other recipients of scheme/restructuring fees; and

- what, cumulatively, any particular creditor(s) stood to get out of the scheme or the wider restructuring that was different from that available to the general body of creditors.

This information will need to be included in the Company’s “Explanatory Statement,” which is issued to all scheme creditors.

The court will pay particular regard to:

- the totality of fees paid/payable (rather than each category of fees separately);

- the size of the fee(s) when compared to the predicted returns offered to all creditors under the scheme and the returns that creditors are predicted to make in a liquidation;

- evidence as to whether the fee includes an “element of bounty” or is in line with market rates; and

- evidence from creditors who do not stand to receive the additional payments.

Annex 1

Annex 2

Class constitution issues

| ISSUE |

DETAIL |

DECISION |

|

Bar date, determination and adjudication procedure |

Whilst in principle the procedure applies to all scheme claims, in practice the claims of the finance creditors are unlikely to be subject to any dispute — whereas the claims of other scheme creditors are strongly contested by the Company. This could lead to greater uncertainty of outcome for non-finance creditors.

|

Noble’s submissions accepted The procedure did not involve different creditors having different rights against the Company. Any differences in the way in which the process affects certain creditors were matters that could be raised as a matter of fairness at the sanction hearing. At the sanction hearing, no creditor raised such issues; the court commented that it had no doubt that the adjudication process was both consistent with established legal principles, and fair. |

| New money debt | Whereas finance creditors are accustomed to providing financial accommodation as part of their core business, for other scheme creditors this was not part of their core business — and therefore they might not be in a position, or would not wish, to elect to “risk participate” by advancing new money. |

Noble’s submissions accepted All scheme creditors were offered the opportunity to “risk participate” in the new money debt (in return for their post-restructuring debt receiving a higher priority); there was therefore no difference between their rights which would necessitate placing the other scheme creditors into a separate class from the finance creditors. The reasons why some scheme creditors might be reluctant or unable to elect to risk participate ultimately relates to their individual circumstances and commercial interests — which are not relevant for class constitution purposes. However, all creditors must be afforded sufficient time to assess the merits of risk participation and find the money to do so. The Company extended the timetable accordingly. The court noted that the Company had gone to considerable lengths to ensure that all scheme creditors who wished to risk participate had the opportunity to do so. |

| Fees |

A variety of fees were payable in respect of the restructuring and/or scheme, to certain (but not all) scheme creditors.

|

Noble’s submissions accepted Despite certain reservations, the court ultimately concluded that the fees were not such as to require separate creditor classes. |

1. Practice Statement issued on 15 April 2002 by the Chancery Division of the High Court, reflecting well-known comments in the case of Sovereign Life Assurance v. Dodd (1892).↩

2. One creditor was placed in a separate class of its own for voting purposes, given its different rights under the scheme. All other creditors voted together.↩

3. Noble convening judgment, [2018] EWHC 2911 (Ch) at [61], citing Re Telewest Communications plc [2004] BCC 342 at [14].↩

4. A similar sentiment was expressed by Hildyard J in Re Stronghold Insurance Company [2018] EWHC 2909 (Ch); the convening judgments in Stronghold and Noble were just days apart. This appears to be a push by the judiciary to adjust the role of the court at the convening hearing.↩

5. This is the regulatory body for takeovers in Singapore. This relates to a waiver granted to the Senior Creditor SPV of a requirement to make a mandatory takeover bid for New Noble.↩

6. Citing Far East Capital SA [2017] EWHC 2878 (Ch) at [14].↩

7. The court gave the example of a claim by a scheme creditor in negligence against an independent financial adviser who had not cautioned against him buying the investment in the first place, aimed at recouping the difference between the original amount paid for the investment and the consideration provided under the scheme.↩

© 2018 KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP. All rights reserved.